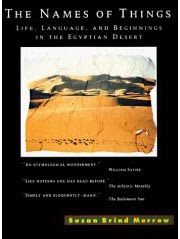

From The Names of Things:

Life, Language, and Beginnings in the Egyptian Desert

by Susan Brind Morrow

I'm halfway through the book. We pick up a book with a certain expectation of what we're in for -- but right now the book seems to be taking me in another direction. I'm trying to withhold my prior expectations and allow the book to unfold itself in my mind.

I keep going back to the first page, the page that caught my attention a few years ago and made me rush to buy the book. The stirring rumination on memory and word:

"You could keep some remnant of it, a talisman that would become rare and fine, worn over time into something familiar. It would naturally become more thin and precious the more the air wore it out, like the bones of a saint. After all, it was only an object in the physical world, not something more potent, like something in the mind: memory.

"But the original, the thing itself, would never come back. It had passed away from the world. You could conjure it, though, the emotion that kept it alive inside you, with a trigger: an image, a smell, a combination of sounds that formed it into a picture that stayed in your mind. That was the life of the thing after it died. The only thing that could bring it back.

"This is what a word is worth."

Some of us write to understand. We use language to give form to evanescent thoughts and emotions, the better to explain, either to ourselves or another. In this sense, language performs a process of crystallization, and we use this process for in our the desire to encapsulate experience. I keep a journal. It is my record of the moments that I want to secure for just that little bit longer.

I have been thinking about this desire in us. Memories will forever be about experience that has passed. Why do we write? Why did we create language? Is it nothing more than a means of capturing something lost?

The truth is I am reminded of something I copied down in my earlier journal a long time ago. That was more than ten years ago, but I wrote it down because there was something about it that felt true, and a little threatening to someone who has depended on the written word. The Egyptian god Thoth gave the science of writing to mankind. Thamus warns of the gift:

"This discovery of yours will create forgetfulness in the learners' souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves. The specific which you have discovered is an aid not to memory, but to reminiscence, and you give your disciples not truth, but only the semblance of truth; they will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing; they will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing;"

~ Phaedrus

I thought this will be a book about writing. It is, in an intimate way -- but it seems to me Susan Brind Morrow also shows how we lost something with our acquired literacy. She tells of the illiterate natives she meets on her travels in Egypt and Sudan, and how she learns a greater appreciation for "something any nomad or illiterate pesant knew; the intangible treasure of memory, of memorized words."

No comments:

Post a Comment