In its press release, the government added that it was now also an offense to import or possess copies of the Hong Kong-based magazine, known by its initials FEER, for sale or distribution in the city-state.

Full write-up here.

“Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try Again. Fail again. Fail better.” ~ Worstward Ho, Samuel Beckett

~ Carrie Brownstein

In its press release, the government added that it was now also an offense to import or possess copies of the Hong Kong-based magazine, known by its initials FEER, for sale or distribution in the city-state.

In The Songlines, Bruce Chatwin observes that nomadic animal species tend to be less dependent upon hierarchies and shows of dominance, since the hardships of the journey naturally weed out the weak. Now that nomadic life rarely involves natural selection, however, travel culture seems to have utilized fashion (among other things) as a subtle kind of litmus test. Ostensibly, a Shan jacket worn with a Mao hat and cotton pyjama bottoms implies that you had the Darwinian oomph to survive northern Burma, communist China, and the Punjab. (Wearing a fanny pack over a lungi, on the other hand, implies that you have yet to prove your evolutionary jam.)

Penguin proudly announces the launch of the Penguin Classics Reading Group @ Amazon.com, a hosted forum to promote lively conversation about selected classics throughout the year. Our discussion of each title will continue for about six weeks, and selections will run the gamut from well-known favorites to cult classics representing writers from across the centuries and all regions of the globe. Please join us as we read great books together!

Came back last night from yoga class and I found the square envelope on top of my laptop. I recognise the roundish handwriting. So, the wedding invitation has arrived.

Some time back, I was at work. There was an old calculator lying around. I picked it up. There was a sticker on the back, with "Unit One" written in a familiar handwriting. It was a distinctive script. Roundish, like something written by the hand of a child. And for a very brief moment there was a tinge of nostalgic heartache.

Has it really been six years?

Of all the people that came and left - it is amazing that you are still my friend.

And now, your wedding.

In case I have to - in case you don't already know I wouldn't miss it unless I'm dead or in a coma:

RSVP - YES. I AM ATTENDING YOUR WEDDING.

I saw that he had changed his clothes: the suit he now wore was even darker than the other one – no doubt true elegance is closer to simplicity than is false elegance, but there was something else about him: at close range, one sensed that the almost complete absence of color from his clothes came not from any indifference to color, but because, for some reason, he deprived himself of it. The sobriety apparent in his clothing gave the impression of deriving from a self-imposed diet, rather than from any lack of appetite. In the fabric of his trousers, a fine stripe of dark green harmonized with a line visible in his socks, the refinement of this touch revealing the intensity of a preference which, though suppressed everywhere else, had been tolerated in that one form as a special concession, whereas a red design in the cravat remained as imperceptible as a liberty not quite taken, a temptation not quite succumbed to.

~ from In the Shadow of Young Girls In Flowers

Still reading In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower.

The narrator is still at Balbec with his grandmother. Saint-Loupe has made his appearance.

And I have finally been introduced to the larger than life Baron de Charlus.

Much have been written about de Charlus - one of Proust's most memorable creations, according to various critics and biographers. I have formed an impression of an aristocratic monomaniac, with an ego as consuming and glorious as the Sun, and everyone else just satellite around him.

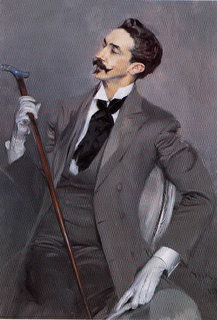

De Charlus is said to be loosely based on Robert de Montesquiou, French Symbolist poet and art collector – and all around snob.

Proust seemed to have fawned on Montesquiou, and it seemed like a calculated relationship for the writer. "Proust was impressed by Montesquiou's combination of reverence for the arts and extraordinary social connections; the young man shared the first and coveted the second," wrote Edmund White.

In fact, White has quite a few things to say about Robert de Montesquiou:

In 1893 Proust met Robert de Montesquiou at the house of the hostess-painter Madeleine Lemarie … Montesquiou – a monster of egotism who needed constant praise as exaggerated as that which Nero had required, and who could be as sadistic as the Roman emperor if it was not forthcoming – was thirty-seven when Proust, just twenty-two years old, met him. In 1909 he gave a hint of his pretensions when he answered a questionnaire (“Who are you?”) by saying: “Related to a large part of the European aristocracy. Ancestors: Field-Marshals: Blaise de Montluc, Jean de Gassion, Pierre de Montesquiou, Anne-Piere de Montesquiou, the conqueror of Savoy, d’Artagnan (the hero of The Three Musketeers), the abbot de Montesquiou, Louis XVIII’s minister, the General Count A. de Montesquiou, Napoleon’s aide-de-camp.” Proust admired his dandy with his leanness (“I look like a greyhound in a greatcoat,” he said of himself), his fabled friendships with legendary poets such as Verlaine and Mallarme, and his cult of the beautiful conducted in his extravagant house, the Rose Pavilion…

Montesquiou was a grand seigneur, distinguished by such overweening pride that a society painter was once overheard saying about him, “There’s one good thing about the French Revolution. If it hadn’t happened, that man would have us beating his ponds to keep the frogs quiet.”

In his high-pitched, grating voice Montesquiou was constantly recited his own poetry from volumes with names like Hydrangeas, The Bats, and The Red Beads, or presiding over literary and musical soirees. No praise was too extravagant, and Proust knew how to lay it on thick. "You are the sovereign not only of transitory, but of eternal things," Proust wrote him. On another occasion Proust (ridiculously) compared him to the seventeenth-century playwright Corneille, the father of Frrench classical theater. But Proust was also the master of the nuanced compliments; after Montesquiou showed him his celebrated Japanese dwarf trees, Proust had the nerve to write him that his soul was "a garden as rare and fastiduous as the one in which you allowed me to walk the other day ..." And Montesquiou heard that Proust kept his friends in stitches imitating his way of speaking, of lauging, and of stamping his foot. Most daring of all, Proust proposed to write an essay to be titled "The Simplicity of Monsieur Montesquiou," who had never been previously accused of such a quality.

~ pp 59-60 from Marcel Proust: A Penguin Life

<--- Portrait of a Snob

In Frank Lampard's book, for example, the long-suffering Chelsea dynamo tells us that during the 2004 European Championship the staff took the players out to McDonald's for a bit of a treat. Not much more is revealed, but those who witnessed the scene claim that there were a few tantrums when it emerged that the toy in David Beckham's Happy Meal was one of the surfer dude turtles from Finding Nemo, while the rest of the squad had to make do with a model of that camp Hispanic crab from Little Mermaid II.

It's kinda surreal seeing your life summarised in 2 big boxes.Only 1 year, girl. Unless they are on strike at East Anglia, then it'll probably be a little longer.

Mr Irwin, a TV personality known as the "Crocodile Hunter", was killed while diving in Queensland when a stingray's barb stabbed him in the chest.

Since then, 10 stingrays have been found mutilated on Queensland beaches.

I decided to take a select few of these popular characters and render their skeletal systems as I imagine they might resemble if one truly had eye sockets half the size of its head, or fingerless-hands, or feet comprising 60% of its body mass.See here.

"There's a line in Turgenev," he says, "That absolutely haunts me. It's a suicide note, and the entire note is, 'I could not simplify myself.' What an arrow through the heart!"

I re-read To Kill A Mockingbird this year. We outgrow childhood books, but there are the special ones that we can never shake off because it was pivotal in shaping the adult you become.

Like Jeanette Winterson, I am uncomfortable with someone who has no books in their homes – because then the person becomes a blank slate to me.

But more than the books you read, what you focus on in a book reveals something about you.

This is one of my favourite parts of To Kill A Mockingbird. I still find it stirring when I read it earlier this year. This is after the "guilty" verdict has been passed on Tom Robinson. Atticus about to leave the courtroom.

Judge Taylor was saying something. His gravel was in his fist, but he wasn’t using it. Dimly, I saw Atticus pushing papers from the table into his briefcase. He snapped it shut, went to the court reporter and said something, nodded to Mr Gilmer, and then went to Tom Robinson and whispered something to him. Atticus put his head on Tom’s shoulder as he whispered. Atticus took his coat off the back of his chair and pulled it over his shoulder. Then he left the courtroom, but not by his usual exit. He must have wanted to go home the short way, because he walked quickly down the middle aisle toward the south exit. I followed the top of his head as he made his way to the door. He did not look up.

Someone was punching me, but I was reluctant to take my eyes from the people below us, and from the image of Atticus’s lonely walk down the aisle.

"Miss Jean Louise?"

I looked around. They were standing. All around us and in the balcony on the people wall, the Negroes were getting to their feet. Reverend Sykes’s voice was as distant as Judge Taylor’s:

"Miss Jean Louise, stand up. Your father’s passin’."

I have always believed this scene is an affirmation. I was looking through my journal, and to this scene, I wrote:

It alway seems silly to cry at this point. But it’s redemptive, almost, this scene. As though it’s never a complete defeat. That in some little way, fighting to the end is its own victory.

With hindsight, I realise that for me, it is not enough to do what is right, just for the sake of doing the right thing. I want the accolades for my struggles.

Like Atticus, I want to be someone who will stand up for a Tom Robinson even if the world tells me not to. But - I want people to stand when I leave the courtroom.

For all the admiration I have of the character, I am not Atticus.

One is about someone else, the other - is about me.

I am still sorely human. And that - is something to think about.

My entry for 15th March 2006, just after I finished reading To Kill A Mockingbird:

Reread the book you loved from childhood, and remember why you loved it then, and why you cry.

That you still can cry at the parts that used to break your heart – maybe you have not lost as much as you supposed. Maybe the years haven’t hardened you so much. Maybe your experience had not caught up with your instincts.

I wonder. Maybe a part of me has not yet changed.

I was browsing through my September/October 2006 issue of Utne magazine. They have included a Mary Oliver poem from her latest collection, Thirst. The collection is due out this October, published by Beacon Press.

I adore Mary Oliver’s writings. I look to her poetry and essays for that breath of fresh air.

Our friendly local library has only one copy of Edmund White's Marcel Proust, and it's categorized under "Reference Only."

What this means is: for the past few weeks, I've been making weekend trips to the library just to read this book.

Gleanings from Edmund White, his take on why we read Proust:

Proust may have attacked love, but he did know a lot about it. Like us, he took nothing for granted. He was not on smug, cozy terms with his own experience. We read Proust because he knows so much about the links between childhood anguish and adult passion. We read Proust because, despite his intelligence, he holds reasoned evaluations in contempt and knows that only the gnarled knowledge that suffering brings us is of any real use. We read Proust because he knows that in the terminal stage of passion we no longer love the beloved; the object of our love has been overshadowed by love itself.

Edmund White has also praised Jean-Yves Tadié's biography of Proust as one of the best on the subject. It is awfully thick, and of course, the genius at our friendly local library has categorized it under "Reference Only."

*sigh*

H’s a nice Australian yoga teacher who came over to teach. How do I know he’s Aussie? Occasionally he comes to class in a singlet with "Australia" printed straight across the back. No one but an Aussie will wear a shirt like quite so unabashedly; feels like someone stuck a "Kick Me" note on his back.

Now, H. is a nice, funny guy who also happens to be a good yoga teacher. He has a slacker-dude sense of humour that I appreciate. His humour and chatter lifts the mood of his classes – important when your muscles are burning from holding the pose.

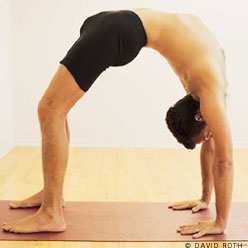

Last Saturday was Power Yoga 1 with H. Personally I find Power Yoga more demanding as I lack upper body strength. Last Saturday we were supposed to do Urdhva Dhanurasana (Wheel Pose). As you can see from the picture, it requires strength in the arms, shoulders and thighs: the areas of the body that I have yet to develop. Baron Baptiste calls it "one of the most powerful poses in yoga practice" – and he meant it.

H. understood not everyone is ready for it, and explained we do not have to try it if we are not ready. The first rule of yoga is Awareness. Be aware of yourself. Know your limits – when to surrender, when to push a little further.

I attempted the Wheel Pose that day. H. saw what I was doing, and he told me to stay down; I was not ready to go up.

When the class prepared to do the Wheel Pose for the second time. H. came over. He asked me to hold his ankles, to give me a better leverage in the arm-lifts. He assisted me in a modified version of Wheel Pose. I was grateful.

Later, addressing the class, H. reminded us that not everyone is ready for all the postures. But he will always allow us the choice to surrender or to attempt the asana. We make the choice. At the end of the day, it is our own practice.

I first learnt yoga more than three years ago in a crowded gym studio. I did yoga 3~4 times every week for more than a year. M, the yoga teacher, was a wound-up core of sheer yogic stamina. Her classes were demanding - and her battle-axe personality was intimidating. She pushed her students, sometimes shouting at them from across the room. I persisted, and because of her I grew stronger. We did Wheel Pose every Thursday. Didn’t matter if you can’t, you just try. If for no other reason, you tried because M was so scary. Then one day, I lifted.

I still remember the first time I went up in a Wheel Pose: The thrilling sensation of power as I pushed my body higher. I wanted to stay in the pose for a long time. My body was light, liberated.

In Urdhva Dhanurasana, I felt like I could fly.

Then I quit the gym. Without the regular yoga practice, I lost the muscular strength. And I couldn’t do the Wheel Pose last Saturday.

But in all that time at the gym, I have never felt so supported and safe - as I did last Saturday in H’s class.

I am grateful to H. – that he saw I was not strong enough, yet supported me in my struggling endeavour. I will continue working at my practice. I will continue to try the challenging poses. And I know H. will watch over me as I explore. I am grateful for a teacher that makes me feel safe.

Most of all, I want to fly again.

"From Turkey to Togo, D.C. to L.A., Rio to Russia and beyond, the Guide promises to recommend the best books -- fiction, history, memoir or otherwise -- to take with you on your travels."

If reading reclaims time, it realigns time too. Time for us is always slipping away — we talk about losing time, finding time, making time, and taking time. The wellbeing that we feel when we don’t notice time, because we are happy, or engrossed or in love, is the result of those rare moments when time inside us and time outside us are not in conflict. Reading is another way of allowing this to happen and, as it becomes a habit, like all habits, it affects the rest of our behaviour too. No question, reading is good for you.I'm feeling that mild distress of "having not enough time." Between work, yoga and the rest of life (this includes chores like laundry) - I find less time to read.